Borobudur, whose name is derived from “Boro” for “big” and “Budur” for “Buddha,” is the largest Buddhist temple in the world. It ranks alongside Bagan in Myanmar and Angkor Wat in Cambodia as one of the great archaeological sites of Southeast Asia.

Borobudur has faced many challenges over the centuries. It was neglected around the 14th or 15th century AD when Hindu-Buddhist civilization began to decline in Indonesia and Islam rose. In 1985, it was targeted by a bomb that destroyed nine stupas and two Buddha statues; the perpetrator was a Muslim preacher. An earthquake measuring 6.2 on the Richter scale struck on May 27, 2006. Before its complete restoration, Borobudur was also targeted by looters who took Buddha statues to sell to antique collectors or museums. Many parts of the temple were lost and diminished due to these looters, which is why many Buddha statues are headless.

Today, Borobudur is completely restored and considered one of the modern wonders of the world. It is a popular site for pilgrimage and is Indonesia’s most-visited monument. UNESCO listed Borobudur as a World Heritage Site in 1991.

Once a year, during the full moon in May or June, Buddhists in Indonesia observe Vesak Day, commemorating the birth, death, and enlightenment of Siddhārtha Gautama, the Buddha.

The temple is estimated to have been built during the glory of the Syailendra Dynasty, between 760 and 830 AD. It likely took at least 100 years to complete and is thought to have been finished during the reign of King Samaratungga.

Archaeological excavations during reconstruction suggest that adherents of Hinduism or a pre-Indic faith had already begun to erect a large structure on Borobudur’s hill before it was appropriated by Buddhists. The foundations are unlike any Hindu or Buddhist shrine structures, suggesting the initial structure is more indigenous Javanese than Hindu or Buddhist.

The original foundation is a square, approximately 118 meters (387 ft) on each side. The temple has nine platforms, with the lower six being square and the upper three circular. It is decorated with relief panels and originally had 504 Buddha statues. The upper platform contains 72 small stupas surrounding one large central stupa. Each stupa is bell-shaped and pierced by numerous decorative openings, with statues of the Buddha inside the pierced enclosures.

The monument’s three divisions symbolize the three “realms” of Buddhist cosmology: Kamadhatu (the world of desires), Rupadhatu (the world of forms), and Arupadhatu (the formless world).

Ordinary sentient beings live in the lowest level, the realm of desire. Those who have burnt out all desire for continued existence leave the world of desire and live on the level of form alone: they see forms but are not drawn to them. Finally, fully enlightened Buddhas go beyond even form and experience reality at its purest, most fundamental level, the formless ocean of nirvāṇa.

Kamadhatu is represented by the base, Rupadhatu by the five square platforms (the body), and Arupadhatu by the three circular platforms and the large topmost stupa.

Borobudur is covered in an astonishing 2,670 individual carvings, a mix of stories and decorations spread over a massive 2,500 square meters. These carvings tell a grand story, with a hidden base depicting the law of karma, followed by a journey through the Buddha’s life and past lives on the lower levels. As visitors ascend, they encounter tales of Sudhana’s quest for enlightenment. The entire experience is designed to be followed in a specific clockwise direction, mirroring the ritual circumambulation performed by pilgrims.

The 160 hidden panels at Borobudur don’t tell one story but act as individual illustrations of karma. Each panel shows a cause-and-effect scenario, depicting bad actions and their punishments, good deeds and their rewards, and everyday life caught in the cycle of rebirth. These panels were once hidden from sight but were photographed and are now on display at the nearby Borobudur Museum. Currently, only a small corner of the hidden base with these reliefs is visible to visitors.

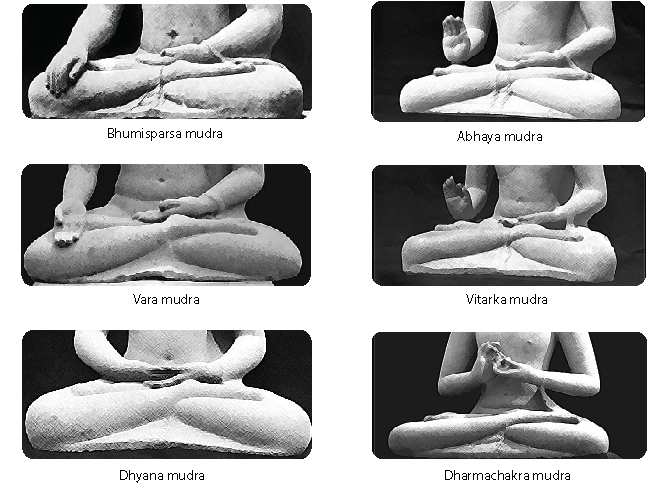

Borobudur’s hundreds of Buddha statues may seem identical but they hold their hands in different mudras: symbolic hand gestures. These mudras represent the five cardinal directions and are associated with specific Dhyani Buddhas and their meanings.

As you walk around Borobudur in a clockwise direction, following the Pradakshina, here’s the sequence of mudras you’ll encounter on the Buddha statues, starting from the eastern side:

Bhumisparsa mudra: Symbolizes calling the earth to witness, representing unwavering determination (Akshobhya).

Vara mudra: Represents benevolence and offering alms (Ratnasambhava).

Dhyana mudra: Represents concentration and meditation (Amitabha).

Abhaya mudra: Represents courage and dispelling fear (Amoghasiddhi).

Vitarka mudra: Represents reasoning and discussion (Vairocana or Samantabhadra).

Dharmachakra mudra: Represents setting the wheel of dharma (law) in motion (Vairochana).

Borobudur is a great destination for photographers. Despite large groups of tourists, you can always find a spot with the right angle to take great shots without people. Many tours organize visits at sunrise, but keep in mind that the last available tour in the afternoon, close to sunset, also provides good lighting for photography.

When planning your visit, don’t forget to buy your tickets in advance, as access to the temple is limited.